Data shows that southern Indian states outshine the rest of the country within health, education plus economic opportunities. But what are the consequences of this phenomenon? Nilakantan Ur, a data man of science, finds out.

Consider a child delivered in India.

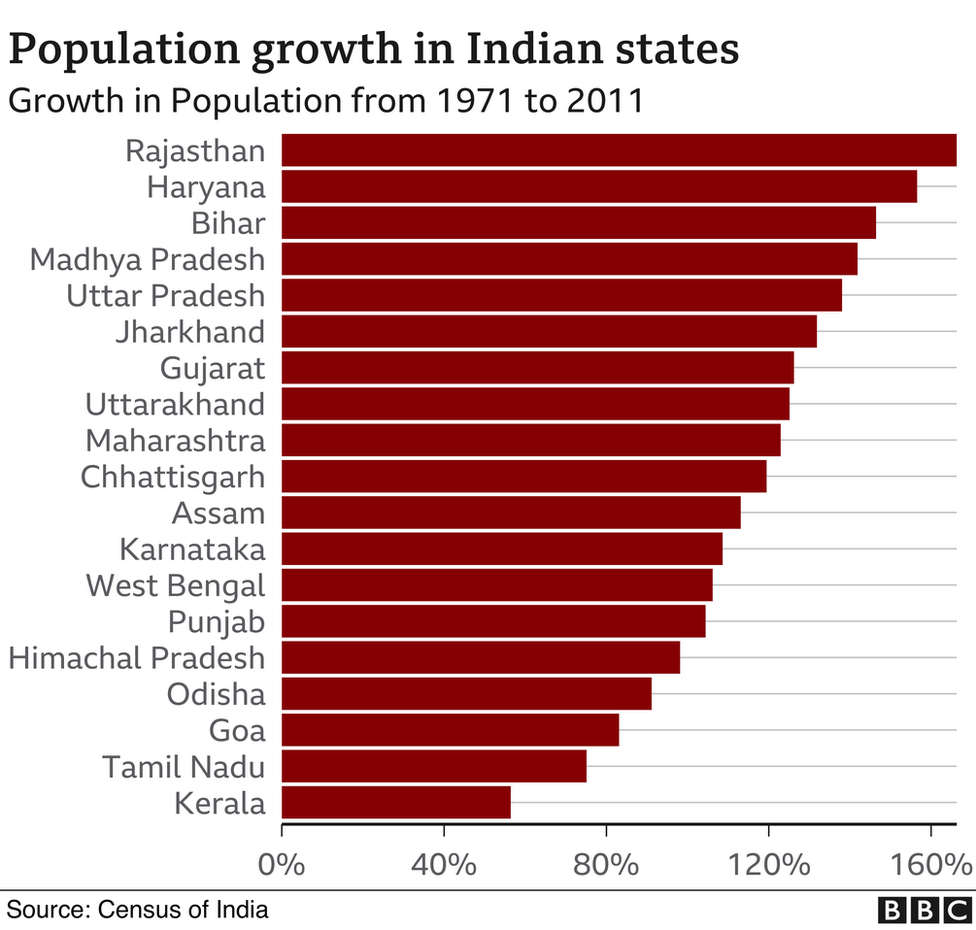

Firstly, this child is far less likely to be born in southern India than in northern India, given the particular former’s lower rates of population development.

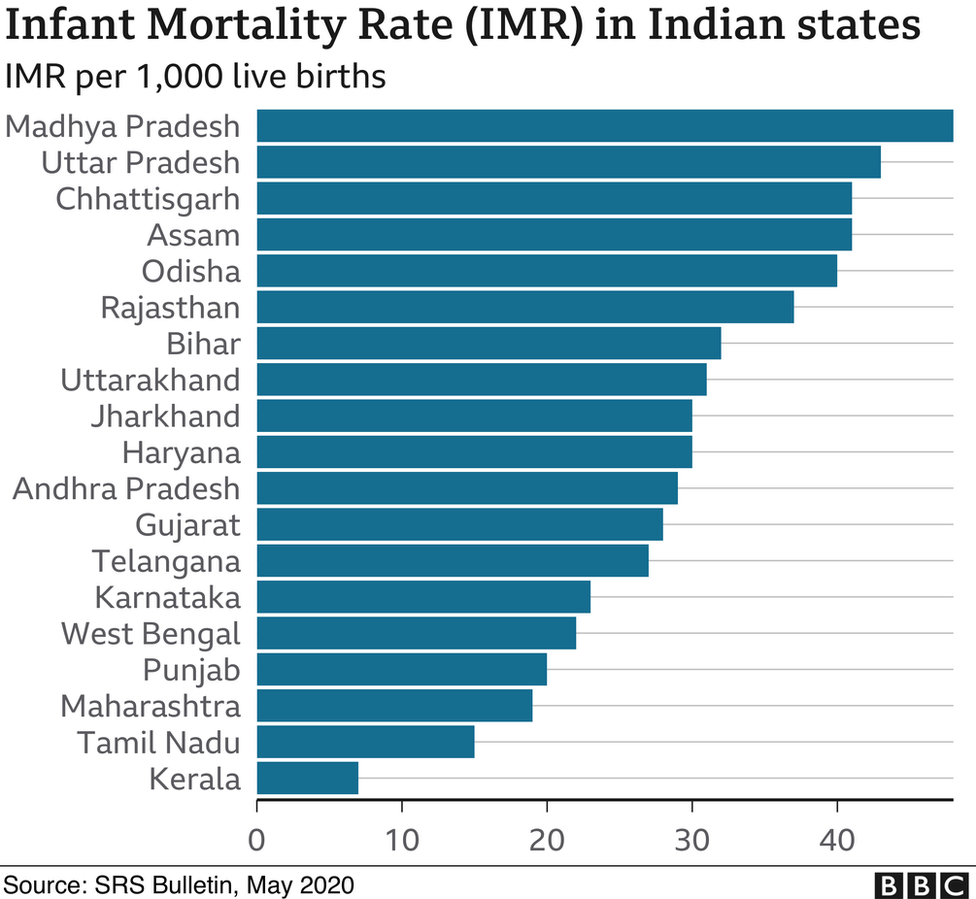

But a few assume she is. Whereby, she is far less likely to die in the first year of her life given the lower infant mortality prices in south India compared with the rest of the country.

She is more likely to get vaccinated, more unlikely to lose her mother during childbirth, more likely to have access to child providers and receive much better early childhood diet.

She is furthermore more likely to celebrate her fifth birthday, find a hospital or a doctor in case she falls sick and eventually reside a slightly longer life.

She will go to school and stay in school lengthier – she will more likely go to college too. She is less likely to become involved in agriculture pertaining to economic sustenance and much more likely to find function that pays her more.

She is going to also go on to become a mother to less children, who in turn will be healthier and much more educated than the girl. And she’ll also have greater political rendering and more impact on elections as a voter.

In short, a typical child born within southern India will certainly live a more healthy, wealthier, more secure and also a more socially impactful life compared with a child born in northern India.

In many of those indicators of wellness, education and financial opportunities, the difference between south and the north is as stark since that between European countries and sub-Saharan The african continent.

But that has not always been the case.

At the time of India’s self-reliance in 1947, the four southern states – Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala and Andhra Pradesh which constituted about an one fourth of India’s inhabitants – were mostly in the middle or bottom part in terms of development. (A fifth state associated with Telangana was formed in 2014 : three years after the final census – simply by bifurcation of Andhra Pradesh. )

However the southern states started to diverge positively compared with the rest of India within the 1980s – a trend which has accelerated ever since.

There is absolutely no one answer to why this happened though.

Each of the southern part of states has its very own particular story, but in essence, the improvement was achieved by the particular innovative policies of individual states.

Some of those worked. Several failed. And many had been fiscally profligate. But the states, many believe, have acted because laboratories of democracy, as they were intended to.

A primary example of this is the middle day meal scheme : feeding students a free lunch at govt schools – which began in Tamil Nadu.

Launched in 1982, the mid-day meal structure ended up increasing college admissions in Tamil Nadu – the state today boasts from the highest school enrolment gains in the country.

In neighbouring Kerala, scholars such as Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen have credited advances in health and education to a combination of political mobilisation and to the state’s syncretic culture. Others for example Prerna Singh, a political scientist, have got cited subnationalism – the strong local identity of the state – as another possible reason.

But the southern part of states’ success has additionally led to a special issue.

The 4 states have a smaller sized population than their own northern counterparts, having seen lower population growth for a generation at this point.

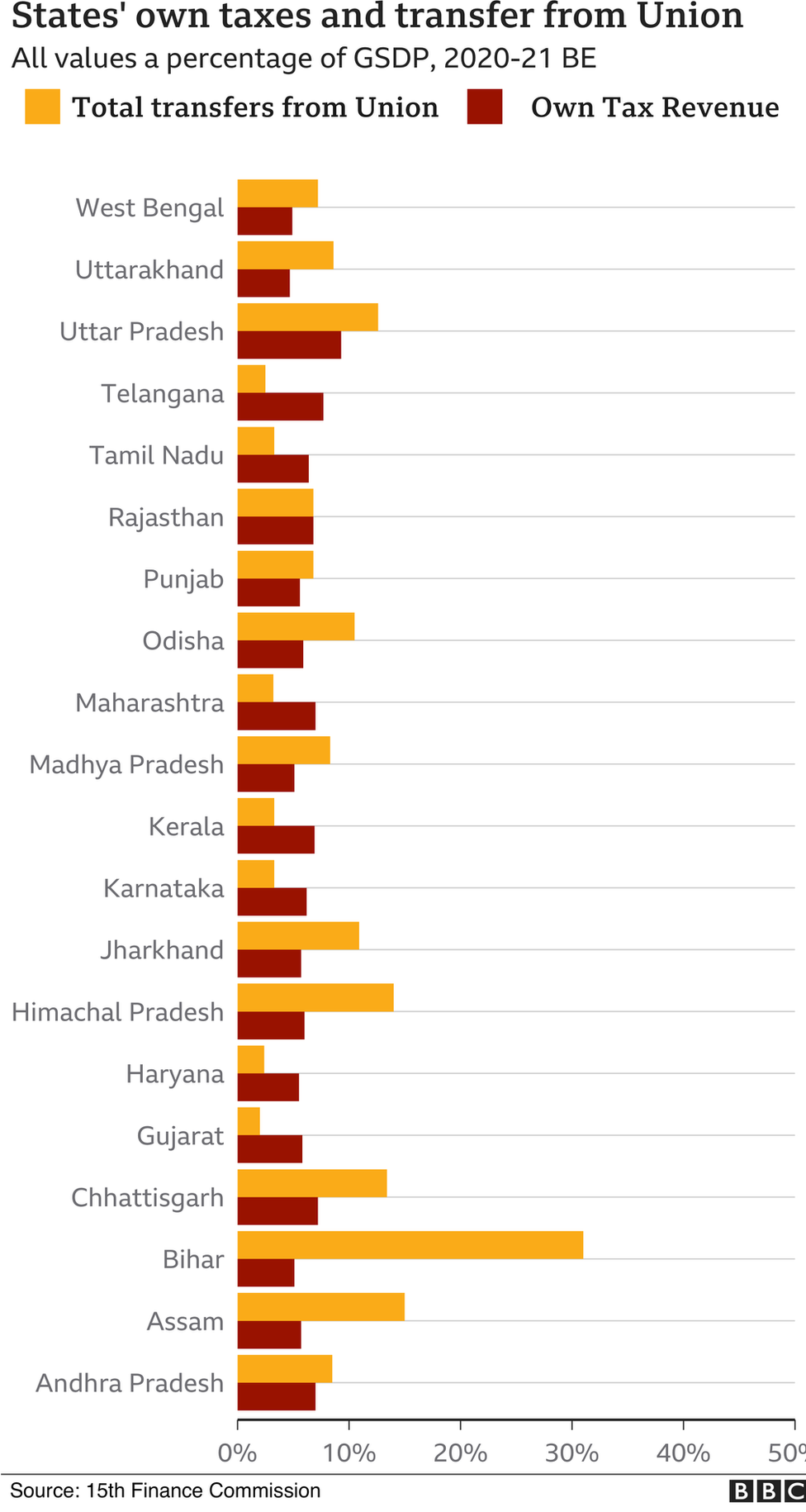

While their own prosperity leads these to being taxed more – on a per-capita basis because they are less populous – they are given a relatively smaller sized share in the central transfer of fees where the amount allocated is dependent on the inhabitants. Thus, they notice themselves as being reprimanded for their success.

A lot of believe that this has happened worse by recent tax reforms.

In the past, all declares would raise revenues through indirect fees which gave all of them the financial freedom to help make their own policies – such as the mid-day meal scheme in Tamil Nadu. But with the introduction of the Goods and Services Taxes (GST), designed to unify the country into a single market, the states say they have little leeway to raise their own finances and so are increasingly dependent on government transfers.

As the Finance Ressortchef (umgangssprachlich) of Tamil Nadu, P Thiaga Rajan said recently, “If you remove all of the variables of taxation away from the says and put them underneath the GST bucket, exactly where are states to find out their revenue plan? You’ve effectively flipped states into municipalities. ”

This has made the relations between your central government as well as the south tense.

In 2020, for instance , after a particularly extented political battle between Delhi and the claims on the GST, the federal government agreed to pay the particular states what it lawfully owed them only after some condition governments threatened to sue.

Earlier this year, there was a tussle between states as well as the central government about lowering fuel costs, with the latter demanding that the states do this – and many of the southern states pressing back.

It’s a problem with no easy solutions.

On the other hand there are people within Uttar Pradesh who would like to be treated similar to a citizen in Tamil Nadu in terms of authorities services and welfare schemes. But on the other hand, there are citizens of Tamil Nadu who finish up sending more money over to states such as Uttar Pradesh than spending on themselves via the complex tax system.

That’s not all : relations between the south and the central authorities could get more filled in the future as the country gears up for an additional round of delimitation in 2026.

The exercise — which was last required for 1976 – refers to redrawing the boundaries of electoral chairs to represent changes in population with time. This means that along with income loss and insufficient freedom to make their own policies, the profitable south may have fewer seats in parliament in the future.

Nilakantan RS is a data scientist and writer of South sixth is v North

Charts by the BBC’s Shadab Nazmi

Read more Indian stories from the BBC:

- Cheetahs make a go back to India after 70 years

- Rape and murder associated with sisters shatters India family

- India Muslim women in limbo after instant divorce ruling

- Story of offences against Indian women in five graphs

- The row over ‘freebies’ within Indian politics

- How families survived when Bangalore drowned

- The British-era colonel revered in India

- India’s Gandhi starts several, 500km walk to bring back party

- Inside India’s ‘factories of death’

Read more about this story

-

-

13 September

-