Three decades on from the nationwide uprising in Myanmar in 1988, the country has been shaken by another whirlwind of contention against military rule. Yet this time it has widened into a revolutionary uproar, which has not abated since the army seized control — again — in February 2021.

Almost two years after General Min Aung Hlaing’s coup d’état shut down a decade of democratic experiments, the opposition to, and resentment against, the new junta is yet to dwindle away. The peaceful — even joyful — popular protests that filled Myanmar’s urban and rural areas after the army seized government in early 2021 were quickly superseded by armed resistance against the new military government.

In stark contrast with the aftermath of the 1988 coup, the resistance has withstood some of the most ruthless counterinsurgency operations ever conducted by the military, especially over the course of 2022.

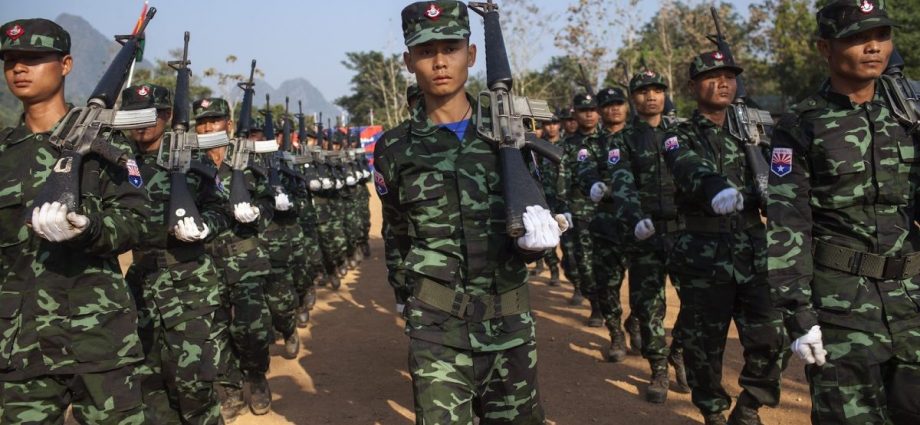

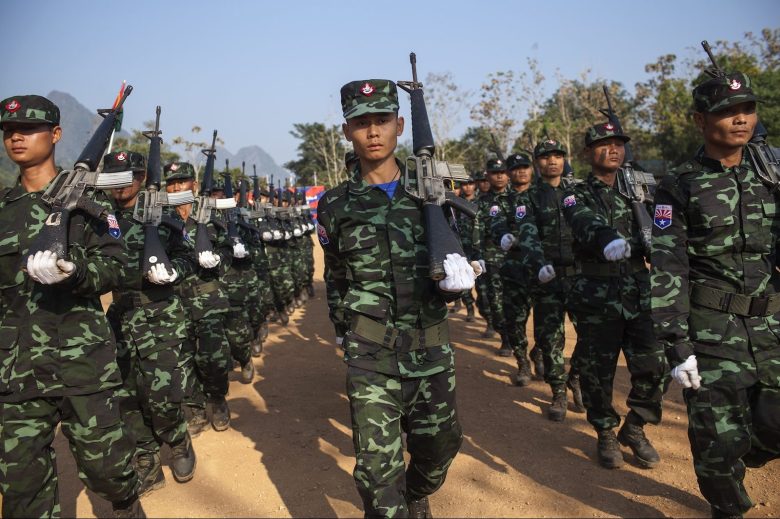

The People’s Defense Forces (PDF) and local resistance groups have mushroomed and effectively engaged in guerrilla warfare up to the point of achieving a dominant position in critical areas during 2022 — in particular in the Sagaing and Magwe regions, as well as in the Chin and Kayah states.

Long-standing insurgent groups such as the Kachin Independence Organization and the Karen National Union have trained and equipped many groups in a coordinated mobilization effort against the armed forces unseen even back in 1988.

Small flash mob rallies against the regime continue to be held on an almost daily basis in villages across the country and boycotting military-owned businesses remains a popular tool of protest.

Defying the military government for the past two years, politicians lawfully elected in 2020, social activists, students and ethnic leaders have gathered around the National Unity Government (NUG) and relentlessly pushed for its international recognition. They have not yet had much success.

But small, if symbolic, victories have recently been won. At the United Nations Ambassador Kyaw Moe Tun — who was appointed by former state counselor Aung San Suu Kyi’s government — is still holding Myanmar’s seat two years after Min Aung Hlaing’s junta sought to remove him.

In December 2022, the UN Security Council adopted its first-ever resolution on Myanmar, expressing deep concerns about the ongoing violence and state of emergency. Although it was non-binding, the resolution urged for the release of political prisoners, including Aung San Suu Kyi, who was recently sentenced by a farcical court to 33 years in prison. Strikingly, neither China nor Russia vetoed the UN initiative.

In the same month, the US House of Representatives passed new legislation allowing for non-lethal American assistance to be delivered to the NUG and other resistance groups in Myanmar. ASEAN has also proved much less accommodating towards the new junta, in stark comparison with the regional organization’s cozy relationship with Than Shwe’s regime in the 1990s and 2000s.

Several leaders in the region have already expressed skepticism about the upcoming general elections planned by Min Aung Hlaing’s government.

Yet there is still little to celebrate two years after the coup. Frustration, if not outrage, at the lack of commitment by the outside world is palpable. In light of what a Western-led coalition has offered Ukraine to defeat Russia’s assault since February 2022, activists from Myanmar have called for similar aid. The anti-junta movement has met with plenty of sympathy worldwide but with little material support apart from the backing of various diasporic communities.

Myanmar’s national economy, already battered in 2020 and 2021 by the Covid-19 pandemic, is now in disarray. Alongside Iran and North Korea, Myanmar is unenviably under international financial watch, because it is blacklisted by the influential watchdog Financial Action Task Force.

People across the country and its borderlands have returned to the informal economy and family networks for survival, while the underground and criminal worlds have blossomed. In the context of brutal repression unabated since the coup, hundreds of thousands of young people have also sought refuge and fortune across Myanmar’s borders as a means to send money back home to their parents.

There has been an unprecedented desire for unity and change among young people and grassroots organizations since the 2021 coup. Social activists, aspiring politicians and students from sexual and ethnic minorities have mobilized in a gripping collective action grounded on common goals of equality, federalism and a future without men in uniforms running the show. This is where the battle lies.

But not everything is as thrilling as a revolutionary call. Cynicism runs deep within a fractured society at war with its soldiers for so many decades. Factional infighting within and between resistance forces, clashes over tactics and dueling visions of democracy remain salient features of anti-coup politics.

What comes next is unclear. There is no indication that the country may quickly move either away from junta rule through a swift military victory of resistance forces, or towards another version of a functioning electoral authoritarian regime guarded by a besieged military.

Across Myanmar’s postcolonial history, its people, whether farmers, students or civil servants, have grown up through cycles of repression and protests. They will, no doubt, continue to rise up in anger and hope in coming months, buoyed by the energy and moral power of legitimate protests against authoritarian rule.

They will also, echoing the two decades of advocacy that followed the 1988 coup, continue to voice their impatience, if not discontent, with a dithering outside world.

Renaud Egreteau is Associate Professor with the Department of Public and International Affairs at City University of Hong Kong. He recently authored Crafting Parliament in Myanmar’s Disciplined Democracy, 2011-2021 (Oxford University Press, 2022).

This article, republished with permission, was first published by East Asia Forum, which is based out of the Crawford School of Public Policy within the College of Asia and the Pacific at the Australian National University.