Envision if you could put an ultra-thin, transparent solar sheet on your own window to generate energy, not just from sunshine but also artificial lighting from inside your area?

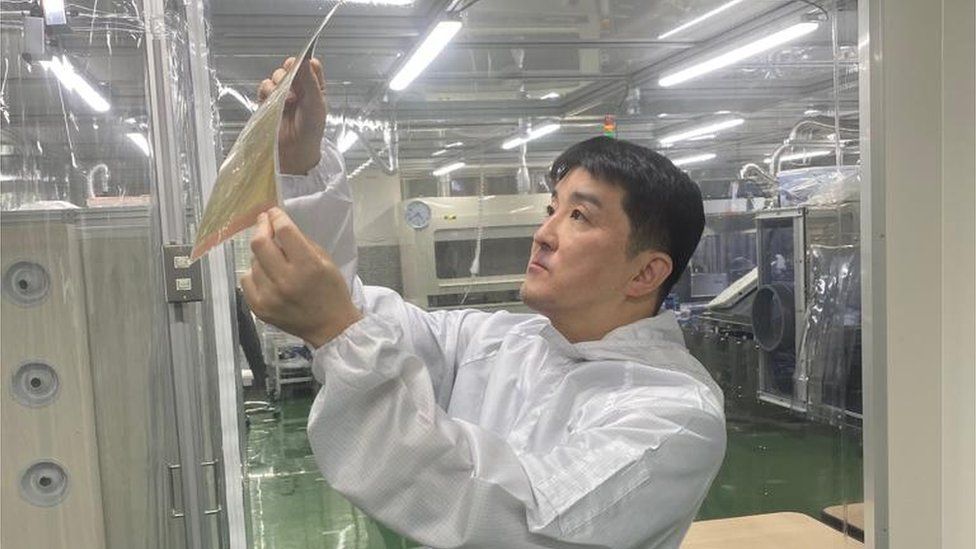

Seen as probably the most promising next-generation sun cell, this technologies, called perovskite, is precisely what Japanese start-up Enecoat Technologies is attempting to develop.

When ready, the Kyoto-based firm hopes the product will create as much power as a regular solar panel of the same size.

“We are hoping to market them in three to four years, ” states the co-founder plus chief executive of the company, Naoya Kato. “But to use them outdoors, we need to make them durable for virtually every kind of weather conditions, to ensure that will take longer. inch

Start-ups such as this are called “deep tech”. They are small firms who are blending high-tech engineering development with scientific finding. The hope is it will lead to the development of transformational products.

Yet a successful product release in this sector requires time. As a result, personal venture capital funds that lend money in order to entrepreneurs may be more cautious to invest in all of them.

That is exactly where Kyoto University performs a crucial role. It could be best known for producing more Nobel prize those who win than any other university in Asia (11 in total), but it also financial situation new start-ups simply by students and experts through its 2 venture capital funds.

Enecoat Technologies is one of the beneficiaries, and has received a total of 500m yen ($3. 6m; £3m). The money came from the $300m fund that the university received from your Japanese government back in 2015 to motivate entrepreneurship.

Frédéric Soltan

“Kyoto University is usually strong in quite difficult science fields such as regenerative medicine, originate cell science, plus cleantech energy, ” says Koji Murota, who heads the university’s Office of Society-Academia Collaboration designed for Innovation.

“But in order to commercialise these types of deep-tech companies it needs a long time and a wide range of money. ”

Mr Murota adds that even though a typical venture capital fund’s investment period might be eight to ten years, that is not long enough to get deep tech, therefore the university’s scheme offers up to 20 years of support.

Since Kyoto University started its innovation department plus investment fund 7 years ago, the number of start-ups created by its learners have more than doubled to 242.

Brand new Tech Economy is a collection exploring how technology is set to shape the new emerging economic landscape.

Which is second only to Tokyo University, which furthermore received similar financing from the government, yet Kyoto University’s growth rate is much increased.

But even before the university started offering support to entrepreneurs, the city of Kyoto was known for creating start-ups. These include Nintendo. It may be a computer online game giant today, but when it launched long ago in 1889 it made playing cards.

One more successful firm placed in Kyoto is technology giant Kyocera, which was created in 1959 with the late Kazuo Inamori, one of Japan’s best-known business leaders.

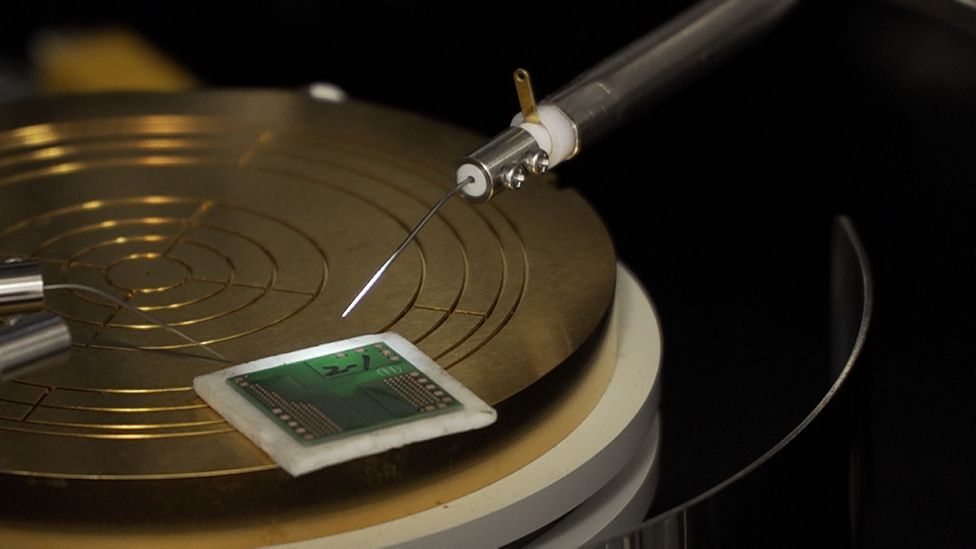

A more current business success story in the city will be microchip manufacturer plus fellow deep-tech start up Flosfia. Also supported by the university, much more semiconductors that specialise in using energy more proficiently, thereby extending the lifespan of the product, such as electric cars.

“Kyoto’s uniqueness has been small and yet varied, ” says Kyoto University graduate and the boss of Flosfia, Toshimi Hitora. “The university is at the guts of it, and with so many researchers in a small community, anyone can accessibility the information you need to start a business.

“But all the Kyoto-based companies’ founders also say that, unlike firms in Tokyo, they don’t have sufficient customers here [in Kyoto], so they needed to think globally right from the start. ”

Mr Hitora adds: “It has been more than 10 years given that we started Flosfia because deep tech takes time, and am feel Kyoto individuals understand that. ”

Some 30 years ago, The japanese was a pioneer in the semiconductor industry, yet today it has lower than 10% market share.

To get Flosfia to establish a substantial presence in the extremely competitive global semiconductor industry, one centered by firms like South Korea’s Samsung and Taiwan’s TSMC, will be a challenge, specifically as China and the US are also seeking to put their stamp on the market.

In the US this move has been led by the Whitened House, with the House of Representatives moving a government action in July that commits a $280bn assistance package for domestic chip production and research. The US wishes to reduce its dependence on additional nations for products.

But Mr Hitora believes that Japan producers like his have their own strengths. “Japan is good in doing basic research, plus working with new components, so I feel we have a big potential, inch he says.

He provides that Flosfia now has alliances with most of Taiwan’s primary chip manufacturers.

“Semiconductors are needed globally, therefore some governments may try to intervene to guarantee the supply for their house markets, but it takes a long time to produce semiconductors, ” says Mister Hitora.

“To bulk produce them, we want a lot of stakeholders and lots of businesses in many nations. That is why I believe our alliances with other companies are important. ”

Because Japan plays catch-up in the semiconductor field, Kyoto University’s ability to patiently play the long game with firms such as Flosfia increases the hope the country will be profitable.

View New Tech Economy Japan on BBC iPlayer