JAKARTA – More than two decades ago, democratic reforms ended the Indonesian military’s dwifungsi (dual-function) role that had underpinned the 32-year rule of authoritarian leader President Suharto since the anti-communist bloodletting of the 1960s.

In doing so, the uniformed branch was effectively removed from the political equation, even if it has retained considerable influence through a nationwide territorial structure and a public image that is second to none.

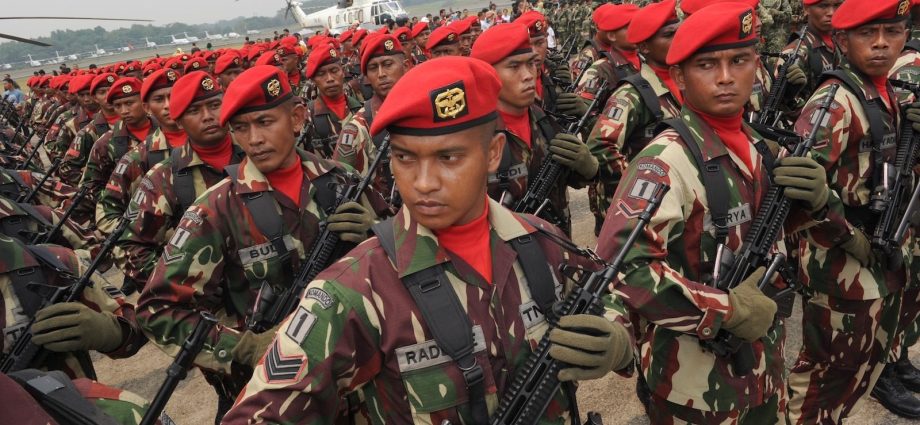

Now, a proposed revision to the 2004 Indonesian Armed Forces (TNI) Law that would dilute the president’s authority over the military and allow more officers to serve in the bureaucracy is causing waves in both military and civilian circles.

Even Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto, a prospective candidate for next year’s presidential elections, doesn’t see the need for tinkering with legislation he feels has been effective in preserving the principle of civilian supremacy.

Some retired generals are opposed to a TNI law at all, arguing that other nations rely not on legislation but on doctrine and protocols to keep their militaries in line. “Why,” asked one three-star retiree, “are they always trying to put us in a cage.”

Dwifungsi was first introduced during a period of martial law in 1957 and then expanded when Suharto took power a decade later to include “every effort and activity of the people in the fields of ideology, politics and economics and in the socio-cultural field.”

By 1980, serving military men held as many as 8,156 positions in all levels of government, from city mayors and provincial governors to ambassadors, state enterprise executives, jurists, legislators and Cabinet ministers.

That had been reduced to about 6,000 in 1995, but despite the reforms that followed Suharto’s downfall four years later, finding jobs for the boys became an increasingly difficult problem in an institution with shrinking duties.

It is unclear who is pushing the changes, but analysts point out that a proposed extension to the retirement age for some senior posts from 58 to 60 would allow TNI chief Admiral Yudo Margono to stay on beyond November when his short 11-month term expires.

Other analysts speculate that the overall move may be a reaction to what one calls “mission creep” by the well-funded national police and their ever-dominant role in the security framework which does not sit well with army generals.

Political activists aren’t pleased at whatever is happening. “The revision of the TNI Law reinstates dual function, violates the Constitution and is betrayal of reform,” the Civil Society Coalition for Security Sector Reform said in a statement last week.

“Instead of promoting TNI as a professional state instrument for defense, the proposed changes will put its reform agenda into reverse,” it said. “We believe some of the changes pose a threat to democracy, a nation of laws, and the advancement of human rights in Indonesia.”

Activists are particularly alarmed about the plan to revoke the president’s prerogative to mobilize and deploy TNI forces, noting Article 10 of the Constitution stipulates that the head of state wields the highest level of authority over the army, navy and air force.

Another article in the 2002 National Defense Law underscores the president’s authority to mobilize the armed forces, despite the head of state not being part of the formal chain of command. He is directly responsible, however, for the police.

The coalition statement said it would be “dangerous” to put the mobilization and deployment of the armed forces outside the approval and control of the president.

“This will certainly restore TNI to the position it once held in the past, wherein it was empowered to act in the face of a threat to security, to undertake a military operation other than war without deferring to presidential decision.”

This, it said, “indisputably goes against the principle of civil supremacy that is fundamental to the concept of a democratic state with regard to maintaining democratic civil-military relations.

Critics are also worried about the new law’s proposed increase in the types of Military Operations Other Than War (OMSP) from 14 to 19, which they say indicates a desire to expand the role of the military beyond the defense sector.

They point out that some of the additions are in fields beyond military competence, including ani-narcotics measures, drug precursors and other addictive substances, and vague missions in support of national development.

A third major point of contention is the plan to increase to 18 the number of ministries where active officers can hold jobs as a way of relieving a logjam in the upper echelons of the 300,000-strong army that has so far defied solution.

Interestingly, the International Institute of Strategic Studies lists Indonesia as having a per capita ratio of one active serviceman per 1,000 population, one of the lowest in the world and on a par with East Timor and Cameroon.

Under the 2002 law, serving officers can currently hold positions in 10 different institutions, including the Defense Ministry, the Political Coordinating Ministry, the National Defense Institute, the National Search and Rescue Agency, the anti-narcotics and counter-terrorism agencies and the Supreme Court.

Although the numbers vary, military spokesmen have said in the past there are about 100 generals and more than 500 colonels who have no designated jobs, many of them so-called “expert staff” on the packed eighth floor of the Defense Ministry.

Apart from an end to dwifungsi, the shortage of positions is put down to a 2005 extension to the retirement age from 55 to 58, fewer internal security threats since Aceh and East Timor, and a failure to retire officers if they don’t make the grade by a certain age.

When the issue surfaced four years ago, there were concerns that discontented colonels might either stray towards religious extremism or shift their loyalty to Prabowo, Widodo’s then-presidential rival and a former three-star general.

But shedding colonels and one-and-two-star generals ahead of retirement – and ending what is effectively a womb-to-tomb vocation – could only worsen morale.

Analysts believe a better way to alleviate pressure at the top may be to reduce the annual Indonesian Military Academy intake of 150-200 cadets and cut back recruitment of specialized junior officers from the country’s universities.

In 2019, as part of a review of the country’s 15 regional commands, Widodo authorized the upgrading of many of the Type B resort commands (korems) to Type A status, but that created only a handful of new positions for colonels and brigadier generals.

Back then, National Defense Institute governor Agus Widjojo described opening up the bureaucracy to more serving officers as a “one-dimensional” plan which ignored the side effects or failed to offer any long-term solution.

“It is not a way to solve the problem of officers who don’t have jobs,” said the retired three-star general who played a major role in getting the military out of politics and is currently the Indonesian ambassador to the Philippines.

Both Western-educated, Widjojo and Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, then chief of staff for socio-political affairs, initiated the first moves to depoliticize the military in 1999.

Over the next two years, the police were separated from the armed forces and active-duty officers were ordered to leave their posts in the bureaucracy and either take early retirement or return to the military, which many did.

But it wasn’t until 2004, just months before Yudhoyono became the country’s first directly elected president, that the remaining military and police appointees were finally compelled to quit Parliament.

The TNI’s pervasive territorial structure remained in place, although Yudhoyono did issue a decree placing all military businesses under the umbrella of the Defense Ministry, saying that command authority tended to destroy good corporate governance.

In the years that followed, the military kept a generally low profile – until successive TNI commanders, first General Moeldoko, now Widodo’s chief of staff, and then General Gatot Nurmantyo, began seeking a wider domestic role for the military and openly talked about their own presidential ambitions.

Fearing it may represent the thin end of the wedge, pro-democracy activists have continued to question why military officers who either retire or voluntarily leave the service opt for a political career, sometimes unreasonably so.

Despite everything, however, the TNI has a far better public image than the national police – or for that matter any other institution. A Kompas survey last February gave it an 86.5% approval rating, with the once poll-topping Anti-Corruption Commission (24%), the Constitutional Court (52%), the police (50%) and Parliament (29%) trailing in its khaki wake.