JAKARTA – After ignoring human rights issues for the duration of his tenure, President Joko Widodo has sprung a surprise by expressing regret for 12 gross violations dating back to the 1965-66 massacre of an estimated 500,000 alleged Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) members and supporters.

But while the unprecedented move will help burnish Widodo’s image, the greatest share of the credit belongs to political coordinating minister Mahfud MD, a former defense minister and Constitutional Court justice who pushed hard to make the historic breakthrough.

It won’t be enough, of course. Describing it as a “half-step,” former Human Rights Commission (Komnas HAM) chairman Marzuki Darusman said the government still must decide whether there will be a judicial or non-judicial resolution to some of the darkest chapters in Indonesian history.

Retired diplomat Makarim Wibisono, who led the 12-man team formed by presidential decree last September to map out a non-judicial settlement, says he only agreed to the task after assuring himself it was not politically motivated.

Many of the victims and their families shared that suspicion. “They thought we were manipulating them for political reasons,” he said, recalling the difficult conversations around some of the 12 incidents that had previously been chosen by Komnas Ham.

Mahfud decided on a different approach after his efforts to create a truth and reconciliation commission, modeled along the lines of similar bodies in Latin America and South Africa in the 1980s, ran into constitutional obstacles that could not be overcome.

“With a clear mind and sincere heart, I, as the president, admit that gross human rights violations have happened in various events and I very much regret that they happened,” Widodo said in his January 12 statement. “I have sympathy and empathy for the victims and their families.”

Other cases can be added to the current list, but Wibisono noted that the December 2014 killing of four people in the Papua town of Paniai, the center of illegal mining operations, was dropped because it had already gone through the legal process with the acquittal of the military officer involved.

While welcoming the latest development, Human Rights Watch (HRW) senior researcher Andreas Harsono called it “too little, too late,” and said if it was going to mean anything it would have to be followed by a process of accountability.

Wibisono says his team worked “day and night” to arrive at a formula acceptable to all members, but he says the way forward depends on the government implementing a series of recommendations that allow for “mutually enforceable” judicial and non-judicial solutions.

The president said the government was trying to rehabilitate the rights of victims, “without negating a judicial resolution,” leaving open how that would be achieved by future administrations.

“Does the president have the political standing to carry this through?” Darusman asked. “It’s not something that can be assured, but at least this will be a bit of solace to victims that their status is recognized. That hasn’t happened before.”

Wibisono says it is crucial to amend parts of the 2000 Human Rights Court Law, which utilizes a criminal process that often deprives the attorney-general of sufficient evidence to prosecute human rights cases.

The team also recommended the government seek parliamentary approval to ratify the Rome Statute recognizing the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD).

Wibisono underscored the need to follow up the committee’s work with “concrete steps,” including the creation of a presidential task force to ensure that its recommendations are being carried out. Failure to do so, he says, “means nothing will happen.”

Mahfud says Widodo will now go on a nationwide tour to show his willingness to tackle the politically sensitive issue and to pledge restitution to the victims and their families.

Already the president has announced he will restore the citizenship of an estimated 500 elderly Indonesians, many of them former students with suspected links to the PKI, who were left stateless abroad after founding president Sukarno was deposed in 1967.

Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi and Justice and Human Rights Minister Yasonna Laoly have been tasked by the president to arrange meetings with the exiles, who live mostly in the Netherlands, Czech Republic, Sweden, Germany, France, Cuba and China.

It was only in the early 2000s that Indonesia scrapped the “EX-TAPOL” stamped on the identity cards of thousands of former political prisoners jailed without trial – letters that condemned them and their immediate families to a life of discrimination.

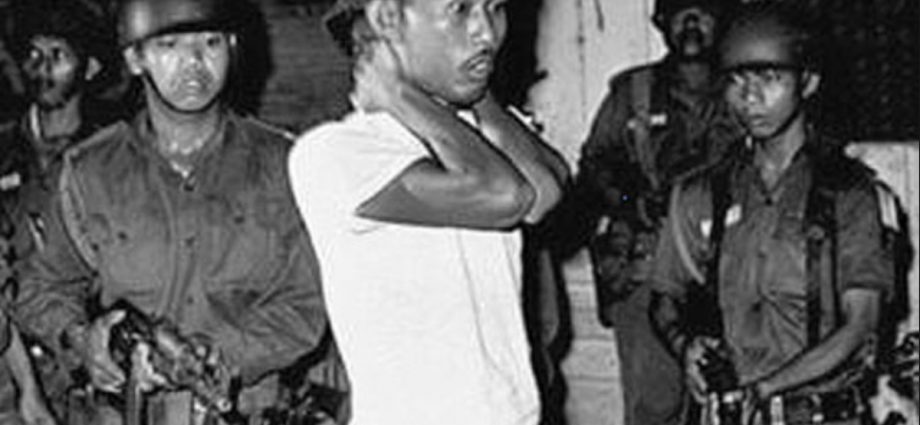

Apart from the 1965-66 purge, the list of atrocities also highlighted the so-called Petrus Killings, a wave of extrajudicial executions of criminals between 1983-85 that claimed up to 10,000 lives.

The other listed incidents include:

* The 1989 Talangsari massacre in Lampung, southern Sumatra in which a battalion of troops killed an estimated 130 followers of a suspected Muslim extremist.

* The systematic torture of separatist rebels at an Indonesian Special Forces (Kopassus) base in Aceh, northern Sumatra, in which victims were raped, buried alive and hung.

* The disappearance of at least 12 pro-democracy activists in 1997-98, some of whom are alleged to have been buried in drums off the Thousand Islands in Jakarta Bay.

* The May 1998 riots which broke out in the days leading up to president Suharto’s forced resignation, leaving an estimated 1,000 dead, many in burnt-out buildings.

* The killing of four students in a targeted shooting during anti-Suharto demonstrations at Jakarta’s Trisakti University in May 1988, the incident which triggered the riots that followed.

* Two separate incidents known as Semanggi I and II in which 29 protestors were shot dead by security forces in the heart of Jakarta in November 1998 and September 1999.

* The mass murders of 100 people accused of practicing black magic during an outbreak of mass hysteria in Banyuwangi, East Java, in 1998-99.

* The killing of 52 people during a peaceful demonstration in Dewentara, North Aceh against an earlier shooting incident near Lhokseumawe.

* The killing of at least four people in a major security operation in Wasior, West Papua in 2001-2.

* The deaths of 50 people during two months of violence in the Papua highlands capital of Wamena in 2003 triggered by a mob raid on an armory.

* The torture and murder of 16 civilians during a security sweep in the South Aceh village of Jambo Keupol village in May 2003.

The main opposition comes from retired generals who argue the government has failed to recognize the PKI’s atrocities, many of them involving the murder of rural landowners who resisted efforts at land reform in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Wibisono says the 1965-66 bloodletting should not be looked at in isolation and that it is important to put it in a broader context going back to 1948, the year troops killed thousands of PKI members in Madiun, East Java.

He notes that no effort was made by the Sukarno government to ban the PKI, which only grew in strength over the next 15 years, winning 16% of the national vote and 30% of the vote in East Java in the 1955 elections.

Then armed forces (TNI) commander General Andika Perkasa announced last April that relatives of alleged PKI members can now join the military, a move that came 18 years after it had been applied to the bureaucracy in a 2004 Constitution Court ruling.

Although polls show 85% of Indonesians do not believe there are any signs of a PKI revival, an underlying communist phobia lingers to this day, stoked by conservative elements anxious to perpetuate the legitimacy of past actions.

In 2007, the Attorney-General’s Office banned dozens of school textbooks that neglected to mention the PKI’s alleged involvement in the events of September 30, 1965, in which six leading generals were abducted and murdered.

Those killings led to the eventual overthrow of Sukarno and the emergence of Suharto, a then-little-known general who was to amass the extraordinary powers that allowed him to rule unopposed for the next 32 years.

In 2015, the Widodo government surprisingly supported a national symposium that year designed to facilitate a first-ever meeting between the military and survivors of the atrocities.

But then the president felt compelled to balance that act of contrition by instructing the security forces to uphold the law against efforts to spread communist teachings by seizing books and items containing hammer and sickle imagery.