Converting people to another religion is illegal in Nepal, but missionaries are willing to risk prosecution to spread the Christian faith.

“Victory to Jesus,” Korean pastor Pang Chang-in cries as he blesses a new church in the village of Jharlang, in the foothills of the Himalayas.

The congregation of the newly converted raise their hands in prayer. Most are from the indigenous Tamang community, who used to follow the Lama faith, an ancient spiritual practice.

In Pang’s eyes the Tamang people are “poor financially and spiritually”.

“So, a miracle takes place and the whole village converts,” he says.

Missionaries, many of them South Korean like Pang, have helped build one of the world’s fastest-growing Christian communities in Nepal, a former Hindu kingdom and the birthplace of Lord Buddha.

Most of the surge in Christian numbers in Nepal is from among members of the community who call themselves Dalits – traditionally at the bottom of the Hindu caste hierarchy – or from indigenous people.

They may believe in miracles as Pang suggests, but for them conversion also offers a chance to escape entrenched poverty and discrimination.

Pang has overseen the opening of nearly 70 churches in his two decades in Nepal, mostly in Dhading district, two hours north-west of the capital Kathmandu. The community, he says, donates the land and Korean churches help pay for the construction.

“In almost every mountain valley, churches are being built,” Pang claims.

That may be an exaggeration, but there’s no doubt there has been a huge increase in the number of churches all over Nepal in recent years. The latest data from the national Christian community survey says there are now 7,758 churches in the still overwhelmingly Hindu country.

And South Korea is behind much of this transformation. It has become one of the world’s biggest missionary-sending nations – only a couple of decades after it started deploying them – with more than 22,000 abroad, according to the Korean World Mission Association.

Driven by the zeal of the born-again, Korean missionaries have become known for aggressively going to, and sometimes being expelled from, the hardest-to-evangelise corners of the world.

Nepal is now a secular state, and the 2015 constitution enshrines religious freedom.

However, an anti-conversion law that came into force in 2018 means anyone convicted of encouraging someone to change their faith faces up to five years in jail.

“We are always working with the anxiety and nervousness we feel from the anti-conversion law,” says Pang’s wife, Lee Jeong-hee.

“But we can’t stop the spread of the gospel because of this fear. We will not stop saving souls.”

The couple used to be bankers. Lee Jeong-hee says it was her husband “who first received God’s calling [and] shortly after God beckoned us to move to Nepal”.

When they arrived in 2003, a Hindu royal family was still on the throne.

“I was shocked to see so many idols being worshipped,” says Pang. “I felt Nepal was in desperate need of the gospel.”

Five years later the 240-year-old monarchy was abolished following a decade of civil war, and a coalition government came to power, declaring Nepal a secular republic in 2008.

“This began the golden age for missionary work,” declares Pang.

He and his wife are part of a community of around 300 Korean missionary families currently in Nepal.

In Kathmandu the Korean community is largely clustered around the southern suburbs of the capital.

None of the congregation are officially missionaries. They’re on business or study visas. Some run restaurants, while others have registered charities.

In the weeks we spent with the Korean missionary community, Pang and his wife were the only ones willing to speak openly. “I’m open to sharing what God is doing in Nepal,” says Pang.

He doesn’t view their work as breaking the law, because in his mind they are not openly proselytising or baptising.

“Our missionary work is not just about us. God is doing the work. We’d like to show how God works through us to create miracles in Nepal,” he says.

The Christian community makes up less than 2% of Nepal’s population – Hindus account for about 80% and Buddhists 9% – but census data reveals its growth.

In 1951 there were no Christians in Nepal and just 458 in 1961. But by 2011, there were nearly 376,000 and the latest census estimates the community is now around 545,000.

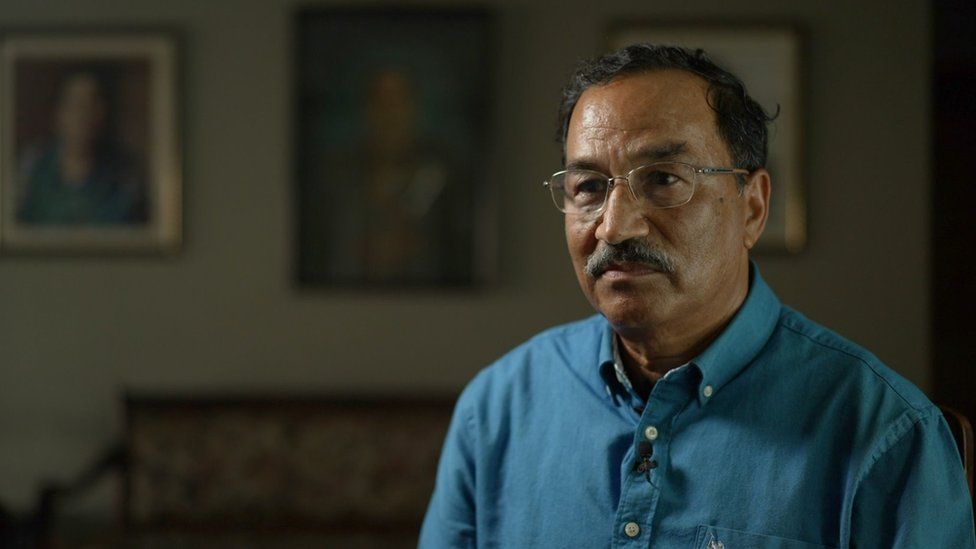

“It’s spreading like wildfire. The cultural identity is at stake. The fabric of the national unity is at stake,” argues former deputy prime minister, Kamal Thapa.

He views the Korean missionary work as an “organised attack on the cultural identity of the country”.

“Missionaries are working behind the scenes and exploiting the poor and ignorant people and encouraging them to convert to Christianity.

“This is not a case of religious freedom. This is a case of exploitation in the name of religion,” he says.

He is lobbying for Nepal to return to being a Hindu state. He supported the introduction of the anti-conversion law and would like to see it being enforced.

It’s only Christians who have been charged under the law, but no-one has been convicted. Cases have either been thrown out due to a lack of evidence or defendants have been acquitted on appeal.

There are currently five active cases, according to the Nepal Christian Society. Charges against four Koreans, including two nuns, were dropped in December.

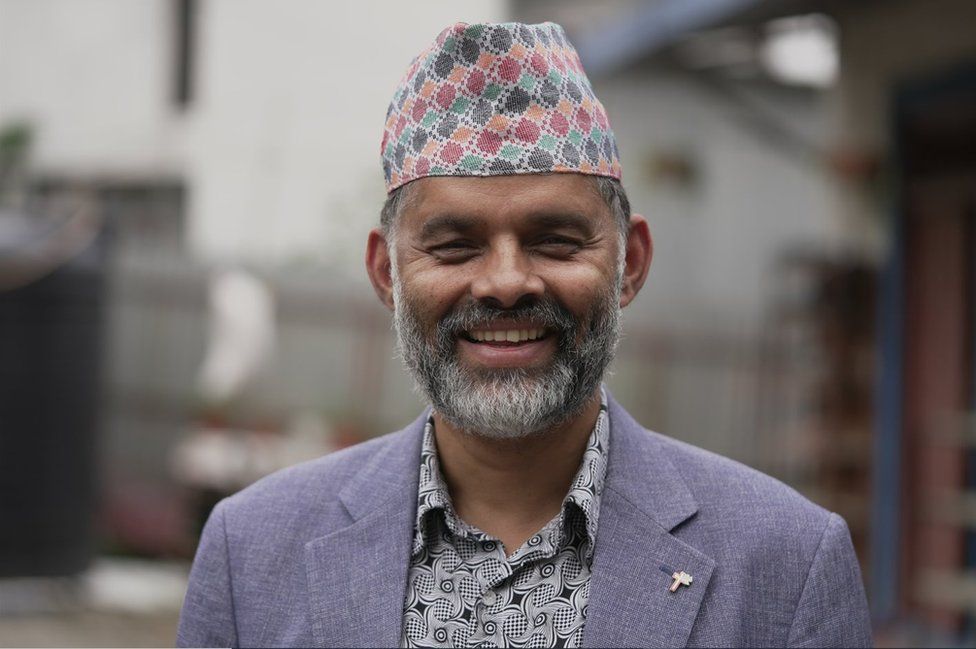

Pastor Dilli Ram Paudel, who heads the Nepal Christian Society, was one of the first people to be questioned under the law.

He was accused in April 2018 of bribing people to convert, something he strongly denies. Charges against him were also later dropped.

“We’re accused of converting people, but that power is not in our hands,” he says.

“If it was, I could convert my mum. She is 92 – I can give her money, I can pray for her, but I can’t convert her because conversion should come from Jesus.”

He comes from a devout Hindu family and was ordained a Hindu priest “like 21 generations before me”. In his 20s he went to study in Korea and that’s where he was introduced to Christianity.

“I was alone and friendless,” he recalls, “and then some people gave me a Korean bible in the Nepali language. Somehow they found the Nepali language one.”

He read it in one night and “found my creator”.

“Does it seem funny and not believable? Well, that happened to me,” he says with a smile.

On his return he was ostracised by his family. “They said Christianity was a foreign religion [and] some people said that I was mad, that I had lost my memory,” he says.

It’s taken time for him to be accepted back into his family and community.

Each year more than 2,000 Nepali students travel to Korea to study. A Korean missionary who spoke on condition of anonymity says they try to connect with local churches in Korea.

“Doing evangelical work within Nepal is a challenge. So we have alternative ways,” he says. “Our mission is to convert – as Pastor Dilli Ram Paudel was a Hindu priest when he was younger – any souls we can, so we must remain under cover.”

Pang and his wife help run a seminary school in Kathmandu. There are around 50 students currently studying. Korean church donors mostly cover the cost of their education and board.

One of them, 22-year-old Sapana, comes from the remote Tamang village of Singang.

“My father loathed churchgoers, as he believed we shouldn’t forget our traditions,” she says.

It was her uncle who introduced her to Christianity when she was gravely ill. She claims she was healed after converting. “I wanted to live for Jesus. Someone finally loved me,” she says.

Remote villages like hers are the new frontier for Korean missionaries like Pang Chang-in.

“In the cities, the anti-conversion law feels much more real. But in the countryside, there are less eyes watching,” says Pang.

Sapana graduated from the seminary late last year. She now plans to return to her mountain village “to slowly grow and push youth to be part of the church”.

“I will go to new places and spread the message of Jesus to those who have not heard it before.”

Pang Chang-in admits the spread of the gospel “can clash with existing religion and culture”.

But his view is that this “culture shock is unavoidable”.

Additional reporting by Rajan Parajuli and Rama Parajuli

-

-

2 October 2020

-

-

-

4 January

-