Getty Images

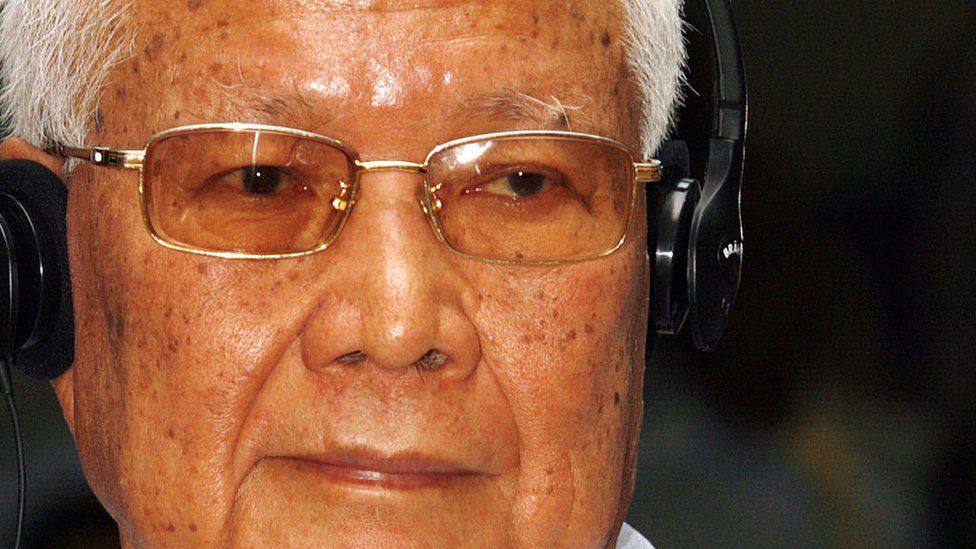

Getty ImagesThe special tribunal in Cambodia set up to examine atrocities under the fanatical rule of the Khmer Rouge has held its final hearing, upholding the 2018 conviction for genocide and crimes against humanity of the regime’s last surviving leader.

Khieu Samphan was one of a small group of Khmer Rouge leaders prosecuted by the unique hybrid court comprised of Cambodian and international judges and lawyers.

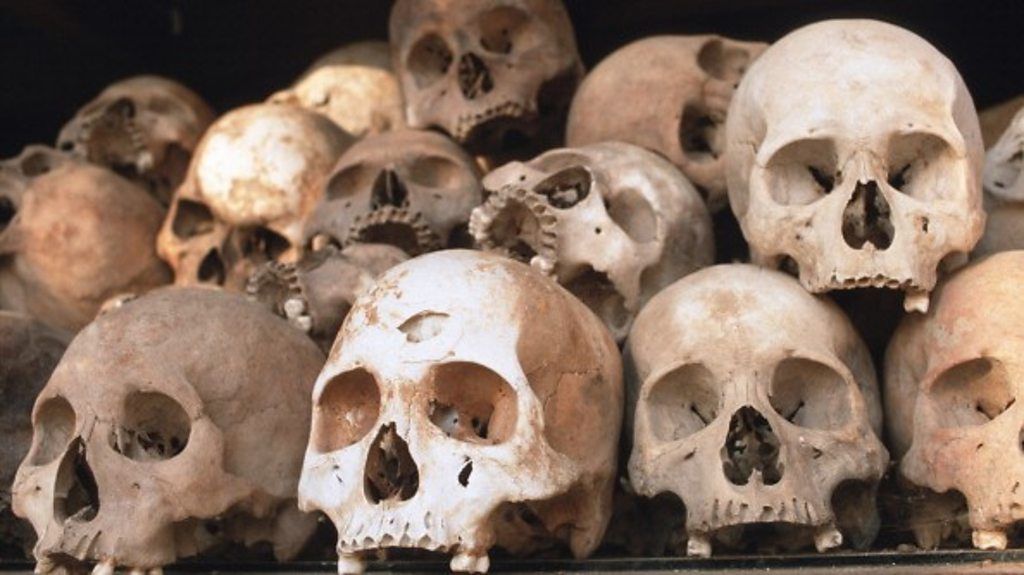

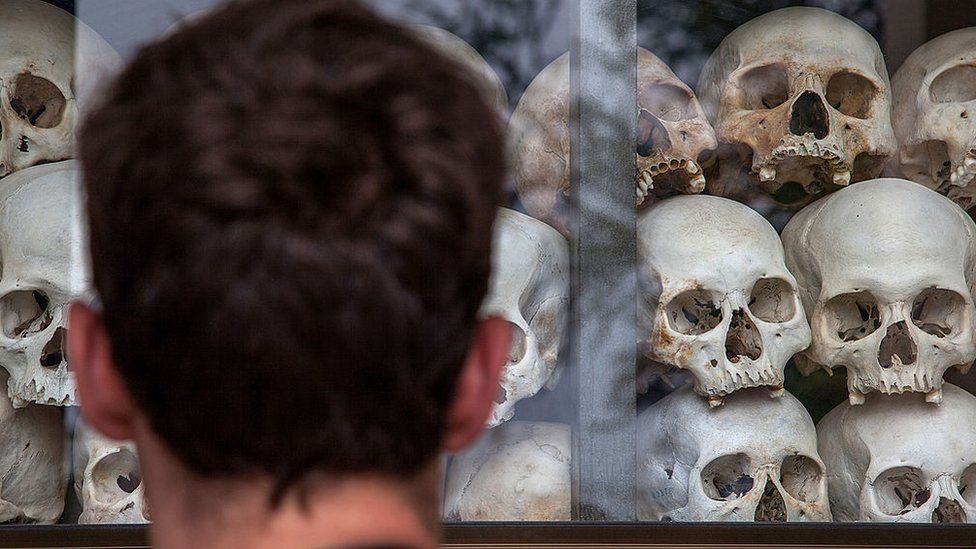

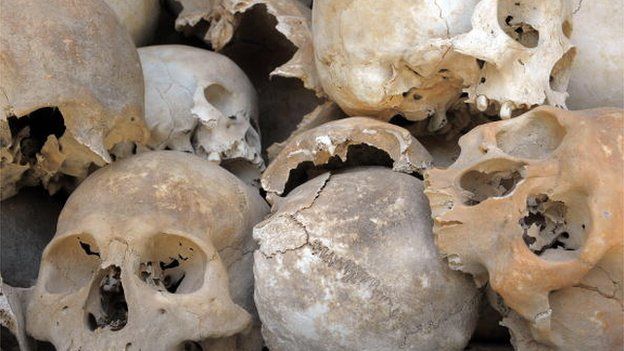

The court’s last hearing ends the official international effort to bring to justice those responsible for the deaths of perhaps two million Cambodians in the late 1970s.

In the end only three people were convicted by the Extraordinary Chambers in the Court of Cambodia (ECCC). It took 10 years to set up and ran hearings for 13 years which cost more than $300m (£265m).

Khieu Samphan’s colleague Nuon Chea, known as Brother Number Two in the Khmer Rouge hierarchy, was arrested in 2007 and given a life sentence in 2014, but died in prison five years later.

The first defendant to be convicted in 2010 was the man known as Comrade Duch, who ran the notorious Tuol Sleng torture centre in Phnom Penh from which only 12 out of 20,000 detainees survived. He died in 2020.

Two other defendants, Ieng Sary, the Khmer Rouge foreign minister and his wife Ieng Thirith, died before their trials could conclude; Ieng Thirith’s trial was stopped when she was diagnosed with dementia.

Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge leader, died in 1998.

International prosecutors at the ECCC had wanted to pursue cases against other Khmer Rouge officials, but were blocked by Cambodian judges sitting on the court.

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen, who was himself a Khmer Rouge military officer until he defected to Vietnam in 1977, argued that going after any more than just the top leaders of the Khmer Rouge risked opening up wounds in Cambodian society, because so many people still living in communities had either collaborated with or been victims of the movement.

Some believed he feared some of his political allies might find themselves in the dock if the prosecutors were allowed a wider remit.

A tribunal borne of optimism

The Khmer Rouge tribunal came out of a uniquely optimistic period in international relations, in the late 1990s.

The end of the Cold War made the pursuit of justice in a country like Cambodia possible for the first time.

Cambodia was the first big post-Cold War international intervention, when it was hoped such operations could both end conflicts and address historical grievances.

This was the time of the special tribunals for former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, and when the International Criminal Court was established.

The political calculations, though, which slowed down the start of the ECCC for years – as the Cambodian government insisted in maintaining a casting vote over most proceedings – were a warning of the difficulties which confront international justice today, when it has proved very hard, for example, to bring the Myanmar military to account for the atrocities against the Rohingya population.

Hope and pessimism

Survivors of the Khmer Rouge have mixed feelings about the ECCC.

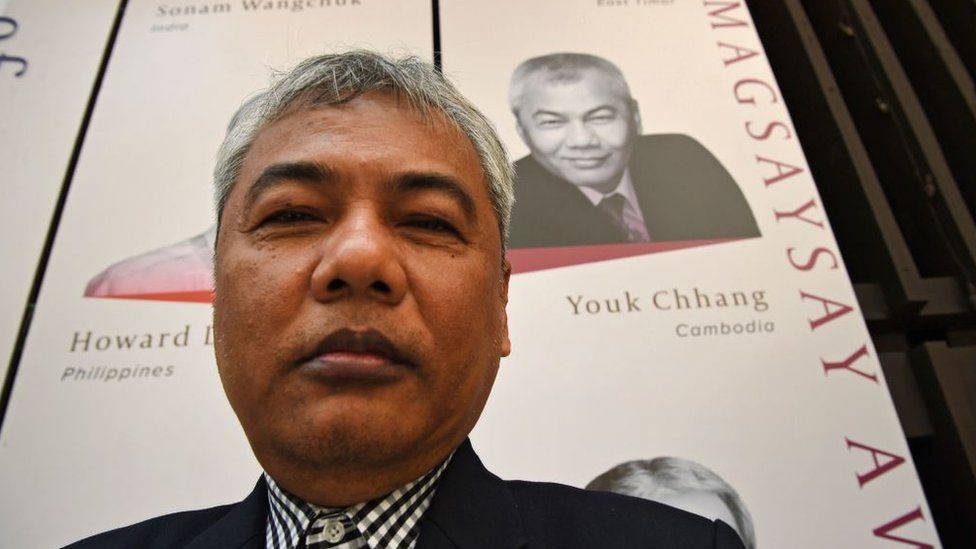

Youk Chhang, who founded the Documentation Centre of Cambodia to keep an archive of the crimes committed by the Khmer Rouge, believes the tribunal has performed a valuable service for Cambodia and the rest of the world.

“It’s a milestone reminder of what happened, and we need that to articulate a more optimistic future for younger generations. I hope that in future smart human rights lawyers will be able to use the investment we put into this court to advance arguments for better human rights protection in front of Cambodian judges,” he said.

“And there have been other benefits. So far we have talked to more than 30,000 survivors about what they went through, and most of them say the court process has been meaningful for them.”

But Ou Virak, a well-known human rights in Cambodia whose father was killed by the Khmer Rouge, and who fled to Thailand as a refugee during the civil war in the 1980s, is not convinced that the tribunal will have a lasting impact.

“We had low expectations. We understood the political nature of the way the tribunal was set up. And all of us involved in human rights issues do care that there has been a tribunal, and some accountability,” he said.

“But we had been hoping it would set the historical facts, and bring about a common understanding of what happened. But the documentation from the tribunal; only really told us what we already know,” said Mr Virak.

“There is a yawning gap still – a silence – between the older generation that experienced the Khmer Rouge, who don’t know how to speak about it, and the younger generation which knows and cares little about what happened to their parents and grandparents.”

You may also be interested in:

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

-

-

30 July 2014

-

-

-

16 November 2018

-

-

-

16 November 2018

-