JAKARTA – After being the focus of dire American travel warnings during more than 15 years of terrorist attacks, Indonesians may be excused for cracking a wry smile now that six countries are doing the same for the United States, the mass shooting capital of the world.

New Zealand, which along with Iceland shares the top two slots in the 2022 Global Peace Index, Australia, Canada, Britain, France, Venezuela and Uruguay have all issued advisories warning their citizens about gun violence when traveling to the US.

They all allude to the prevalence of gun ownership – and the absence of controls – blamed for the 200-plus mass shootings so far this year in which four or more victims have been killed or wounded, excluding the shooter.

Australia tells its nationals that gun crime is possible anywhere in the US and advises those living there to learn active shooter drills. “There is always a risk of being in the wrong place at the wrong time,” the advisory says.

That’s Canada’s line too, reminding citizens that “frequent mass shootings occur, resulting most often in casualties.” Britain says “violent crime, including gun crime, rarely involves tourists, but you should take care walking in unfamiliar areas.”

Venezuela is an anomaly, its travel warning apparently a reaction to the US placing it on its “no go” list – one reason perhaps being it has one of the world’s highest homicide rates.

While mass shootings may have fallen slightly in the US last year, the Kentucky-based non-profit group Gun Violence Archive has recorded 600 cases in each of the last three years in the only country where the number of weapons outnumbers the population.

So far, few tourists have been affected, but as with the immediate impact on tourism from past terror bombings in Indonesia and violent military coups and other actions in Thailand and the Philippines, perception is everything when it comes to personal safety.

Take Bali, ghost-like after the October 2002 bombings, but still managing to stay afloat commercially during the two-year Covid-19 pandemic when 109,000 foreigners elected to stay on and sit it out.

US citizens are probably safer from random violence in Indonesia and Thailand – and even in the trigger-happy Philippines, a former colony with a penchant for copying America’s bad habits – than at home unless stupidity becomes a factor.

The Global Peace Index ranks Indonesia in 47th place, far ahead of the US, which lies in 129th position behind Zimbabwe and Azerbaijan and ahead of Brazil among 163 countries.

Singapore is best among the Southeast Asian nations at ninth, trailed by Malaysia (18), Vietnam (44), Laos (51), Timor Leste (54), Cambodia (63), Thailand (103), the Philippines (125) and Myanmar, unsurprisingly, at 139.

American commentators like to think their country is as safe as anywhere, and probably is. But rates of lethal violence – and a willingness to shoot first and ask questions later – are far higher than in other developed nations thanks to its 2nd Amendment, which protects the right to bear arms.

According to Wisevoter, the gun death rate in the US in 2022 was 4.1 per 100,000 people, leaving it in 32nd place behind El Salvador (35.5), Venezuela (32.7), Guatemala (28.2), Colombia (24.8) and Honduras (20.2) – all known for their drug trafficking and violent crime.

The Philippines leads the way in Asia in 21st place with 8.28 per 1,000. The 9,028 deaths make it sixth in the world, but still far behind Brazil (47,510), Mexico (20,509) and the United States, where two-thirds of the 13,001 deaths were by suicide.

Photo: AFP/ Noel Celis

Thailand, home of the Petchburi hired gunmen made notorious internationally by the film “Bangkok Dangerous”, is in 47th place with 3.1 per 1,000, though its 2,351 gun deaths put it 12th in the world.

Indonesia, which doesn’t have a gun culture, places 187th globally. It had a firearm death rate in 2022 of only 0.06 per 1,000, a breakdown indicating that most of the 153 fatalities were caused by either accidents or suicides.

But Islamic extremist groups are still active, both from inside and outside Indonesia.

Early last month, three Uzbeks linked to the al-Qaeda-affiliated Katiba al Tawhid wal Jihad escaped from a North Jakarta detention center after stabbing to death two immigration officers. A fourth Uzbek died from a head injury in the escape attempt.

The three escapees were recaptured, and investigations are now focused on whether they entered Indonesia intending to attack the Israeli football team, which was due to take part in the now-canceled FIFA Under-20 tournament.

Indonesian authorities were alerted to their presence by US intelligence, which tracked them from the Afghanistan capital of Kabul via Dubai in the United Arab Emirates.

Later in mid-April, two terrorists were killed and four arrested in a rare shootout with Detachment 88 counter-terrorism officers in the southern Sumatran province of Lampung.

In December 2022, in another sign that terrorist cells remain a security threat, a suicide bomber attacked a suburban police station in Bandung, killing one policeman and wounding 11 others.

Although deradicalization efforts have been notably ineffective, terrorism expert Sydney Jones says the global decline of the Islamic State (ISIS) and effective police work have been the major factors for the current lull.

In fact, ithas now been more than five years since the last major incident, in the East Java port city of Surabaya in 2018 where the simultaneous bombing of three churches left 28 people dread, including 15 victims and 13 attackers.

Even after the first string of bombings by the newly-emerged Jemaah Islamiyah terror network in 2000, which claimed 35 innocent victims, it took the Megawati Sukarnoputri government two years to acknowledge it had a home-grown extremist threat on its hands.

In August 2001, US ambassador Robert Gelbard directed the evacuation of all dependents and non-essential staff in response to intelligence reports of a planned Yemeni double truck bomb attack on the embassy.

When an equally complacent City Hall refused his request to build a bomb-proof wall along the mission’s street frontage, he had to settle for giant reinforcedflowerpots instead. The alert level remained high as a result, exacerbated by the 9/11 attacks that year.

Gelbard’s successor, Ralph Boyce, recalls a group of Bali hoteliers coming to see him in late 2001 asking the embassy to exclude Bali from its travel advisory because as a Hindu enclave nothing would ever happen there.

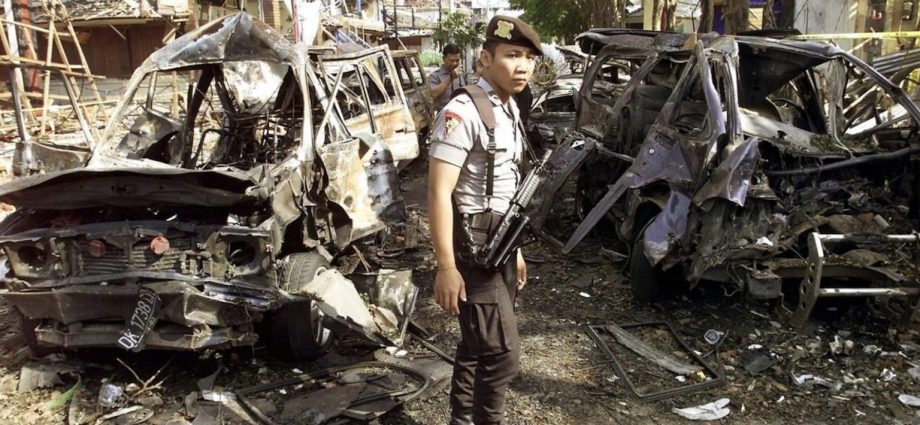

Exactly a year later, the twin bombings of two packed nightclubs on Bali’s tourist strip killed 202 people, including 164 foreigners, in the worst terrorist outrage since the 2001 attacks in New York and Washington.

Seven further attacks followed in Bali, Jakarta and Central Sulawesi between 2003 and 2009, claiming another 82 lives and leaving scores wounded, mostly in hotels and markets.

The US currently lists Indonesia at Alert Level 2 (exercise increased caution due to terrorism and earthquakes) on a color-coded scale where four is the highest.

But it does advise against any travel to Central Papua and Highland Papua where security forces have been trying to secure the release of a New Zealand pilot kidnapped by Papuan rebels last February.